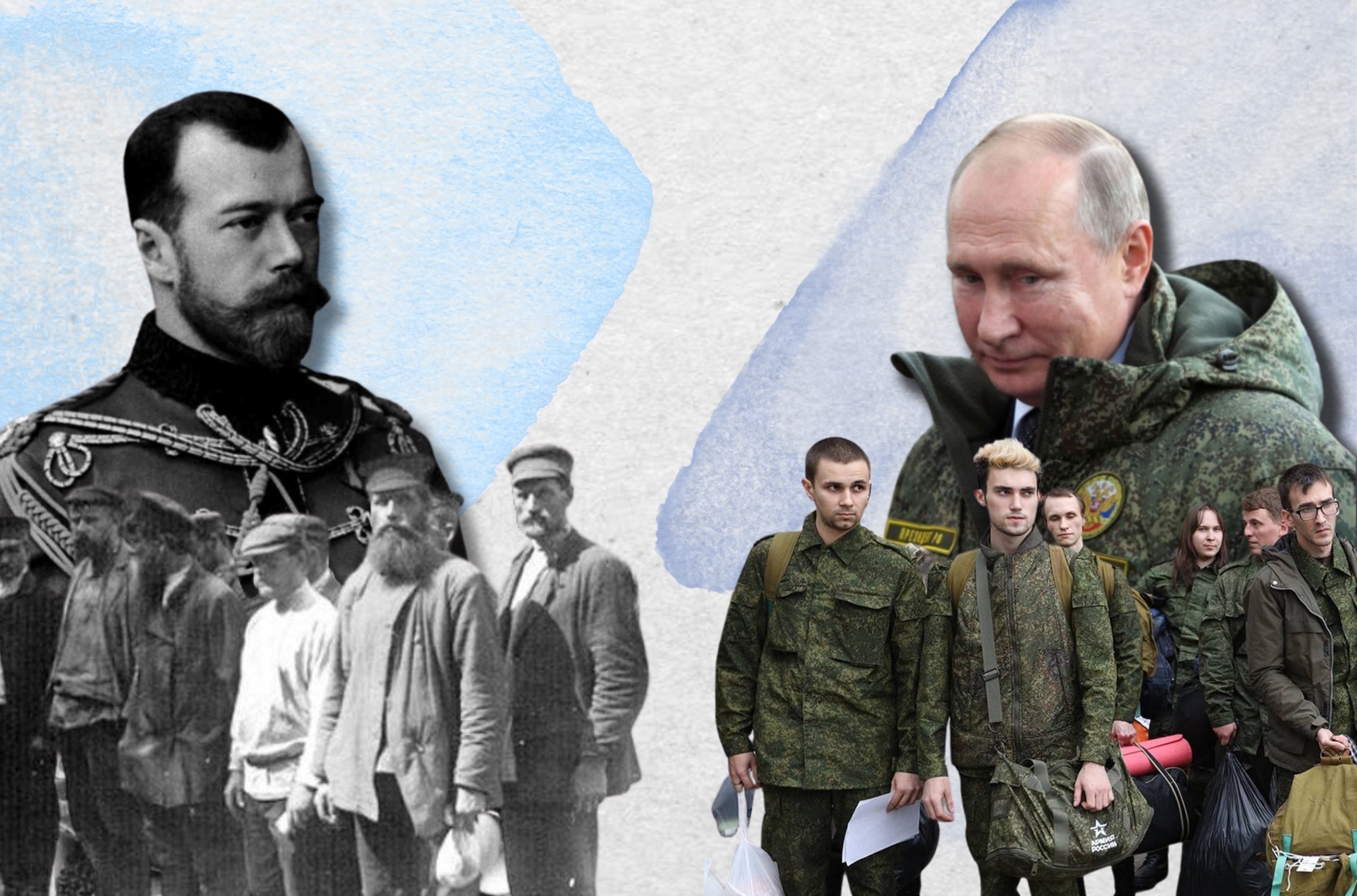

As Putin's army is taking a beating in Ukraine, Russians are bracing themselves for a new wave of mobilization. A century ago, Russia went through a similar phase during the WWI mobilization, when soldiers were reluctant to join the fighting due to a sense of aimlessness, food and equipment shortages, and incompetent commanders. Back then, the discontent ended in mass desertion and a revolution.

Content

The nation's first response to mobilization

Riots and looting of liquor stores

A common cause?

Bashkirs and Tatars serving the Tsar and armed anti-government uprisings

Arming the nation

The nation's first response to mobilization

The Russian Empire joined World War I on its fifth day, on August 1, 1914. However, nationwide mobilization was announced two days prior, on July 30. Another five days prior, on July 25, several military districts near the state border had already introduced “The Decree on War Preparation Period”.

When Russia joined the fighting, patriotism surged. At least some of its urban population firmly supported the idea of protecting the “brother nation of Serbia.” Civil society organizations, State Duma parties, and the Church urged Russians to consolidate around their government ahead of the war. A host of rallies supporting Russia's involvement in the conflict took place in many large cities. On August 2, 1914, Nicholas II solemnly declared Russia's entry into the war from the balcony of the Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg to the enthusiastic crowd in the square below. On August 4, the royal family arrived in Moscow, to be welcomed by at least half a million of its residents.

Nicholas II solemnly declared Russia's entry into the war from the balcony of the Winter Palace

The populace was prone to bouts of xenophobia towards Germans, which sometimes escalated into violent attacks on stores, coffee shops, and other establishments held by entrepreneurs with German last names. The sentiment climaxed in the attack on the German Embassy in Saint Petersburg on August 4, 1914.

In the early days of the war, Russia's vanguard consisted of its regular professional army, which was reinforced with recent reservists to meet wartime objectives. The rise of patriotism led to many military enlistment stations exceeding their targets in the first days of the mobilization effort. G. Patrushinsky, a well-known attorney at law from Irkutsk and reserve warrant officer, sought the “highest” permission for a transfer to a Siberian rifle regiment en route to the frontline “to wrestle the Jewish nation free”. Subsequently, he was decorated with multiple military awards, the highest being the Order of Saint Vladimir in the Fourth Class.

Russian infantry marching on a road in Poland. Early stage of WWI, 1914

In the years that followed, the army made up for its losses by drafting young recruits without prior army experience. Importantly, the drafting age was gradually lowered from 21 to 18 years old. Furthermore, the army summoned more and more cohorts of reservists from among those who’d served years or even decades ago. Finally, they turned to reservists who’d never been in the army because of exemptions. Outside war, such personnel could only be engaged in the rear, but shortages of fighters on the frontline forced the command to send them to the trenches too. In all, Russia mobilized around 15 million people in World War I – over 9% of its population at the time.

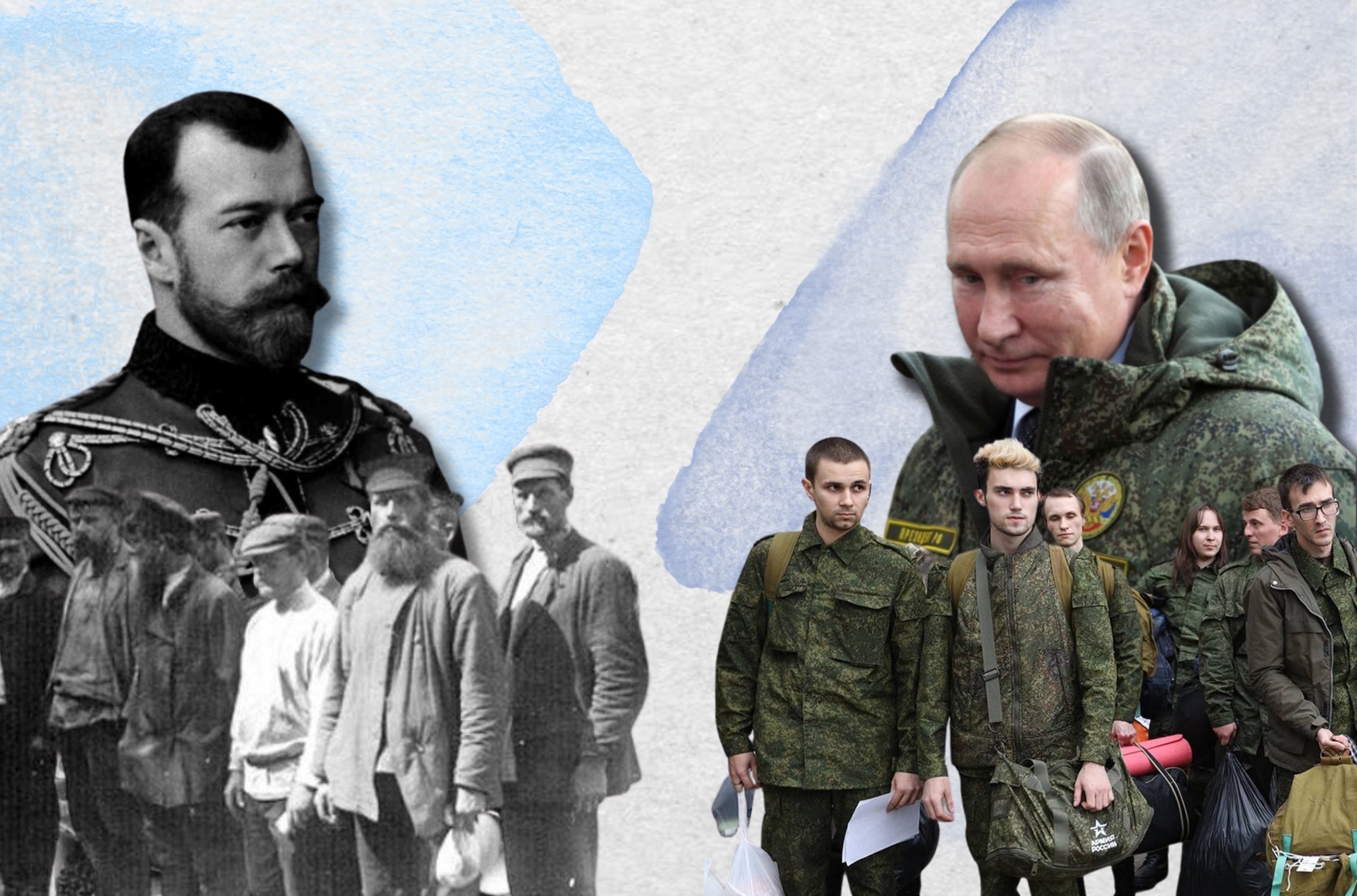

Riots and looting of liquor stores

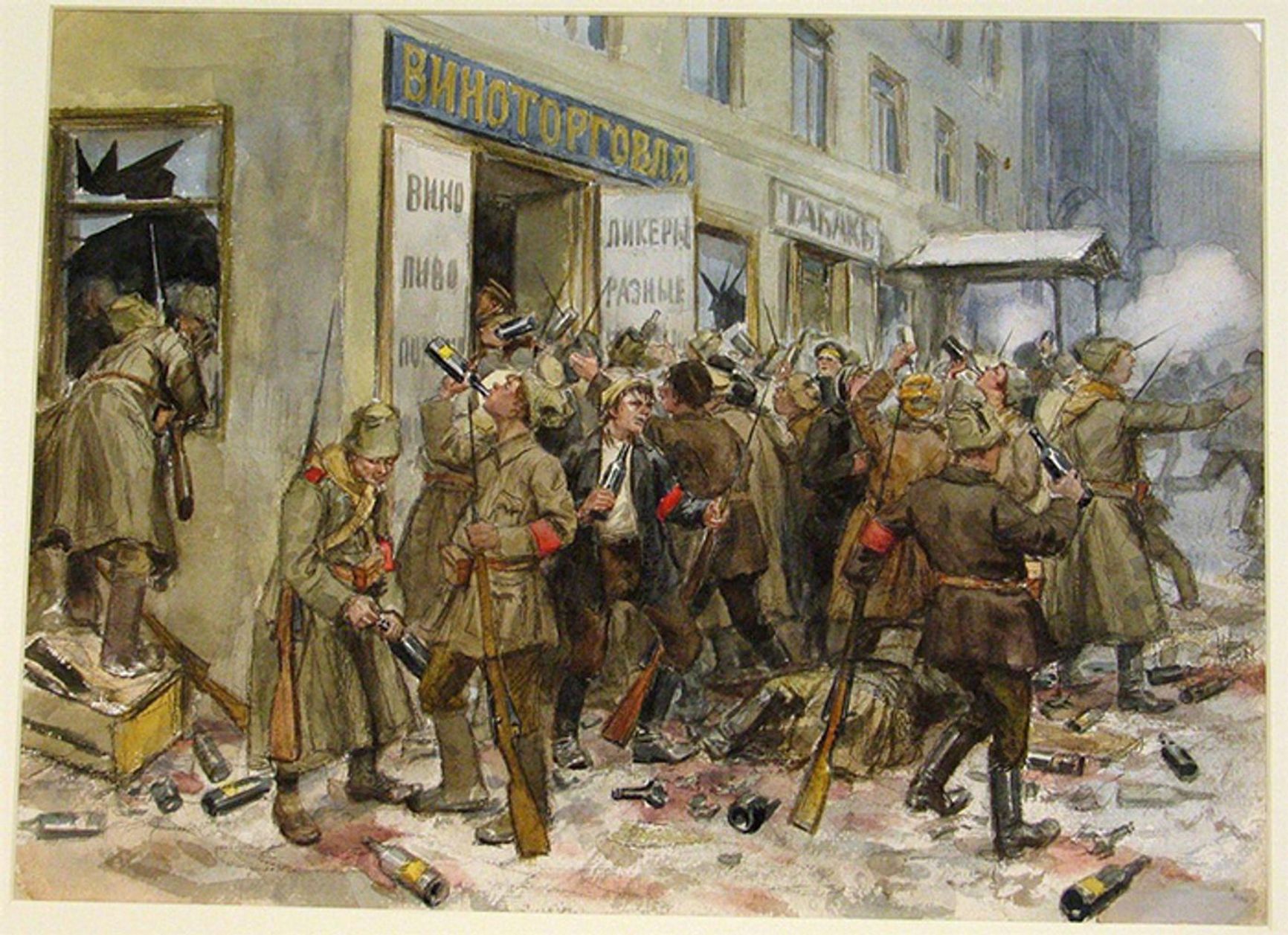

Despite the generally patriotic attitude prevalent among the educated strata of society, far from everyone in the Russian Empire was gunning to join the army. Just a few days into the mobilization, officials faced multiple refusals to join the fighting, which sometimes escalated into riots, including armed violence and destruction of property. Angry mobs burst into the offices of municipal authorities, beat up officials, and ravaged groceries and liquor stores Thus, on August 3, recent recruits wrought havoc on the village of Shakhovskoye near Barnaul, breaking into the municipal administration and the homes of the village chief and the clerk. In the village of Pavlovskoye, reservists ravaged the forester's counting room. On the same day, August 3, Novonikolayevsk (currently Novosibirsk) saw a military uprising that ended in bloodshed. Four thousand mobilized troops were headed from the railway station to the military enlistment office when a group of workers joined them halfway. Hearing shots from the police, the crowd robbed a weapons store and opened return fire. The police called in soldiers of the local garrison for reinforcement. Two mobilized were killed in the shooting, and two dozen soldiers and a policeman were wounded.

Another incident occurred on August 5 outside Novonikolayevsk. A train with mobilized soldiers was about to depart when another shooting flared up, taking the lives of 16 and leaving 25 wounded. Blood was spilled on the same station just a day later. Reservists were banned from leaving the train during the stop but disobeyed, which resulted in a shoot-out with the detachment sent to discipline them: nine killed, over 20 wounded. In response, the government pulled additional units to maintain order on the railroad from Barnaul to Novonikolayevsk.

Initially, the empire imposed a temporary restriction on liquor trade in the regions undergoing mobilization. However, as early as on August 16, 1914, Nicholas II ordered to extend the ban on the sales of pure alcohol, wine, and vodka products for local consumption up until the end of the war. The imperial decree prohibited selling alcoholic beverages in shops, railway station lunchrooms, and groceries whenever drafting was in progress.

By banning alcohol, the government attacked the long-standing tradition of send-off feasts. Frustrated reservists began looting and ravaging liquor stores. In the cossack settlement of Zerendinskaya in the territory of modern Kazakhstan, locals tried to rob the same liquor shop three times. The man guarding the shop, Captain Sushkov, managed to fend off the crowd twice, but on the third attempt, the already inebriated reservists fought their way into the shop. The captain was so outraged that he shot himself in the temple. The shocked crowd slowly began to disperse. Miraculously, the shot wasn’t fatal.

Another booze-related incident took place in the village of Taishet. Taking a taste of the looted goods, the reservists set out for the railway station. They grabbed two rifles and started shooting chaotically. The riflemen who were at the station managed to stop the mayhem, heavily wounding one of the reservists and getting others to scatter.

Havoc in a Liquor Store

Ivan Vladimirov

The first weeks of mobilization were rife with such incidents all over the empire, including the governorates of Vitebsk, Astrakhan, Vologda, Vyatka, Ekaterinoslav, and more. Available reports suggest that 51 public officials and 136 rebels were killed. Other sources set the death toll at nine public officials and 216 rebels. However, there is an alternative body count: in the period from August 1 to August 13 alone, 505 mobilized troops and 106 officials were killed in 27 governorates.

A common cause?

Another hurdle faced by the Russian command was the shortage of weapons and food on the frontline. The nation turned out unprepared for a mobilization of such scale. The barracks where the innumerable recruits were stationed during training struggled to provide them with enough food, clothes, and footwear. Their living quarters were poorly equipped too.

What is even worse, they were sent off to war without proper training. Most recruits spent their six weeks of training learning to walk in formation and cramming the manual instead of learning to shoot and dig trenches. Sometimes new detachments didn’t master basic combat skills until the last day before deployment.

A string of defeats and the ineptitude of commanders, whose misinformed decisions ended in a colossal loss of life, made soldiers feel they’d been dragged into a purposeless massacre. In his book titled “My Recollections. The Brusilov Offensive,” General Aleksei Brusilov remarks that soldiers could not grasp Russia's goals in the war:

“Even after Russia declared war, reinforcements that were arriving from inner Russia were completely oblivious about the origins of the war that had befallen them – out of nowhere, as they saw it. Every time I asked in the trenches what we were fighting for, the answer always went along the lines of ‘someone shot some fancy duke and his wife, so the Austrians had some beef with the Serbs’. However, hardly anyone knew who the Serbs were, or even who the Slavs were, and as for why the Germans had gone to war because of Serbia, no one could tell.”

Being away from home put soldiers under immense pressure. Villagers took it the hardest because no one at home could cultivate such labor-intensive crops as flax and potatoes in their absence. Late in 1916, workforce shortages in agriculture became a national issue, saddling the government with a dilemma: new rounds of mobilization could leave the country unable to feed both the army and the rear. Many of the families that were left without a breadwinner struggled to make ends meet even with their benefits. As a result, many women in cities sought employment as laundresses, cleaners, shop assistants, or utility workers, while continuing to take care of their children and do the chores.

Many of the families that were left without a breadwinner struggled to make ends meet even with their army benefits

The general impression that soldiers’ lives were worthless led to mass surrendering. It became particularly noticeable when the regular pre-war army became scarce due to huge losses and had to be reinforced with barely-trained youth and “old men” in their forties.

Army units refusing to follow officers’ orders to attack, acts of latent and open insubordination were typical of the Russian army throughout the war, peaking in late 1916 – early 1917, when cases of disobedience sometimes involved the use of force and even weapons. Mostly, soldiers were frustrated with poor logistics, high losses during attempted offensive operations, and long periods without rest. “We aren't going forward but we won’t give up an inch to the Germans.” “We want to serve, we can go into battle right this moment, but we won't sit in position,” soldiers protested. Commanders cracked down on open riots, executing “instigators” through court martial. However, firing squads didn’t help, and by the end of 1916, the army was in deep decay. The number of deserters fleeing from military echelons headed for the front grew manifold.

By 1917, army failures had cost Nicholas II, who'd assumed the rank of Supreme Commander in Chief, what was left of his popularity. After his abdication, the most ardent haters of the empire began destroying the symbols of the “damned past,” taking their swords to the crowns on Russia's coat of arms, taking down the portraits of the emperor and his wife in railway cars, and covering up two-headed eagles. Judging by military censorship reports issued in the spring of 1917, the general attitude in the army also changed. For some, changes in the high echelons of power meant a quick victory over the enemy, while others were preparing to take a stand for the newly won freedom. However, their notion of freedom was aligned with the particulars of their worldview. They saw their commanders as representatives of the old government and wanted to exact revenge. Soldiers became insolent with their officers, demonstratively forgoing the military salute, talking back, and openly violating the regulations.

The concepts of patriotism and homeland security were filled with new social and political content that had nothing in common with the patriotic sentiment of the early days of WWI. After February 1917, soldiers got a new incentive: they fought for their freedom – even in their convoluted understanding of it. Rejecting old authority and reveling in their social revanche, “free” servicemen wrought even more havoc on the army apparatus.

Moreover, a failed offensive attempt undertaken by the revolutionary government led to a wave of desertion, refusals to join the fighting, and riots in the rear and on the frontline. Riding the wave of the anti-war sentiment, the Bolsheviks seized power. The imminent collapse of Russia's frontline defense forced them to sign the separate Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the Germans, withdrawing from the war and giving up some of the Empire’s territories.

Bashkirs and Tatars serving the Tsar and armed anti-government uprisings

During WWI, Russian authorities engaged the indigenous peoples of Siberia and the inhabitants of Central Asia – so-called “non-Russians”– in the war effort for the first time in history. Under the 1874 act on universal military service, the only ethnicities drafted into the army were those that had become part of the Russian Empire long ago, like the Bashkirs and the Tatars. They served in the army on the same terms as the rest of the imperial subjects. However, there were two more categories of aliens. The first was called “the wanderers” and included the Mansi, the Nganasans, the Chukchi, and the Khanty. Those weren't drafted at all. As for the other group, “the nomadic aliens”, such as the Kazakhs and the Buryats, they weren't drafted up until WWI because of the stereotypical misconception of them being unable to handle military discipline. However, after sustaining immense losses in 1915, the Russian army was faced with personnel shortages. To remedy the situation, the government started drafting 18- and 19-year-olds. Further on, in June 1916, the Ministry of Interior sent a circular letter to the far reaches of the empire, obliging local authorities to “requisition” property from aliens. Normally, the government confiscated food and cattle to provide for the army's needs. Now it came for the people. However, indigenous Siberians and Central Asians weren't sent to the frontline. Their purpose was to support the army by working in the rear. Thus, Buryat recruits were brought to Arkhangelsk to help rebuild the seaport that was being used for arms deliveries from Russia's allies. They also worked at defense enterprises, manufacturing cartwheels, reins, and horse collars.

Up until WWI, Russia didn't draft Kazakhs or Buryats into the army. They were believed to be incapable of grasping military discipline

July 1916 saw an uprising that engulfed Northern Kazakhstan and Central Asia. Unrest flared up in Khodjent (currently Khudjand, Tajikistan), where locals demanded that the list of the mobilized be destroyed. Tashkent, the capital of Russian Turkestan, was also among the first epicenters of the rebellion. Another major riot took place in Jizzakh, followed by an uprising in the Semirechye Oblast, a region of the empire with the capital in Verniy (currently Almaty). Several thousand armed men captured a post station on the road from Verniy to Pishpek (currently Bishkek), cutting all communication between the cities. The rebels were joined by Chinese volunteers and received weapons from Turkey. Heavy fighting continued for two months in the vicinity of Lake Issyk-Kul in Kyrgyzstan. Russian Turkestan imposed military law. Untrained, poorly organized groups of rebels struggled to counter regular Russian army units. Yet the authorities failed to put an end to the uprising with the use of local forces only, so the high command had to bring several units from the frontline. Militia recruited from among local Cossacks and Russian settlers also helped. Eventually, the armed rebellion was violently crushed. The remaining insurgents sustained a final defeat in January 1917. The overall death toll of the rebellion stood at 100,000-500,000.

Arming the nation

The Central Asian rebellion remained unprecedented in Russia until the end of WWI. However, at the end of the war, the Bolshevik and the White governments were faced with another challenge: men returning from the frontline brought their firearms and kept them at home for a long time. Applications varied, with hooch stills being among the most popular. Peasants had to build spirit stills from scratch, and most featured an element called the worm – a coiled length of pipe. Pipes were in short supply, so craftsmen began using rifle and carbine barrels. Peasants also stored weapons in hopes of once converting them into money – by selling them as scrap metal, for instance. One way or another, WWI army rifles were a common sight in Russian villages, contributing to the growth of the crime rate, among other things.

The possession of firearms also played its part when White Army admiral Alexander Kolchak came to power. In the fall of 1918, his White government in Omsk gave up hopes for a volunteer army because no one was eager to abandon peaceful life. The authorities announced a drafting campaign, enlisting around 200,000 men in Western Siberia – not because of Kolchak's popularity but rather due to the local habit of following government orders. White authorities mostly drafted young men, not those who’d fought in the recent war. The mobilized were sent to the barracks for military training. However, equipment was once again a major issue. Two hundred thousand recruits had to make do with 80,000 coats, 40,000 pairs of high boots, and 20,000 pairs of valenki (traditional winter felt boots). When one-half of the mobilized marched in the training yard, the remaining half had to sit around in the barracks, barefoot. The poor organization caused young guys to scatter back to their villages. In response, the Kolchak government sent punitive detachments. If deserters took to the woods, the authorities punished random locals by flogging them or taking them hostage. At that point, the firearms peasants had been keeping since WWI began to make a difference: Siberia saw numerous cases of guerrilla resistance. The White government did its best to confiscate weapons from the population, but it didn’t always succeed, and the rifles were often used against Kolchak's death squads. Eventually, when the Red Army began its offensive in the Urals, Kolchak’s Siberian army started to disintegrate and fall apart. As they were retreating through their home regions, most of the mobilized peasants from the Urals deserted. In July 1919, the White Army also saw the desertion of the majority of soldiers recruited in the Irbitsky Uyezd of the Perm Governorate. Kolchak’s army soon sustained ultimate defeat, followed by the admiral's arrest in January 1920.

The Red Army also found arms-bearing peasants problematic. Resistance to the confiscation of food and other arbitrary measures of the new government often took a violent turn comparable in scale to major operations of the “greater” Civil War. Naturally, former WWI fighters who’d returned from the trenches with firearms and munitions played their part.